The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) published its 2021 World Economic Outlook and confirmed the exceptional nature of this recovery with unexpected forecasts. The OECD forecasts a 5,8% increase in world GDP, which is 0.2% more than the March estimation.

2020 has not been without difficulties for the world economy, which has shrunk by 3.5% following the crisis we are experiencing. Activity slowed, offices emptied and time stood still as people shut down. Following an unprecedented year, an extraordinary recovery is expected this year. Laurence Boone, the chief economist of the OECD, announces that “if vaccination accelerates and people spend the money they have saved, the growth could be even stronger” and she adds: “it is the highest figure since 1973”.

Nevertheless, the recovery will not be homogeneous and although most advanced economies are expected to return to their GDP levels by the end of 2022, countries like Argentina are expected to wait more than 5 years. As noted earlier, countries that have rapidly vaccinated their populations against COVID19 and can control infections have better conditions for economic recovery. Resumption will be exceptional if countries demonstrate effective and broad vaccination programs and public health policies.

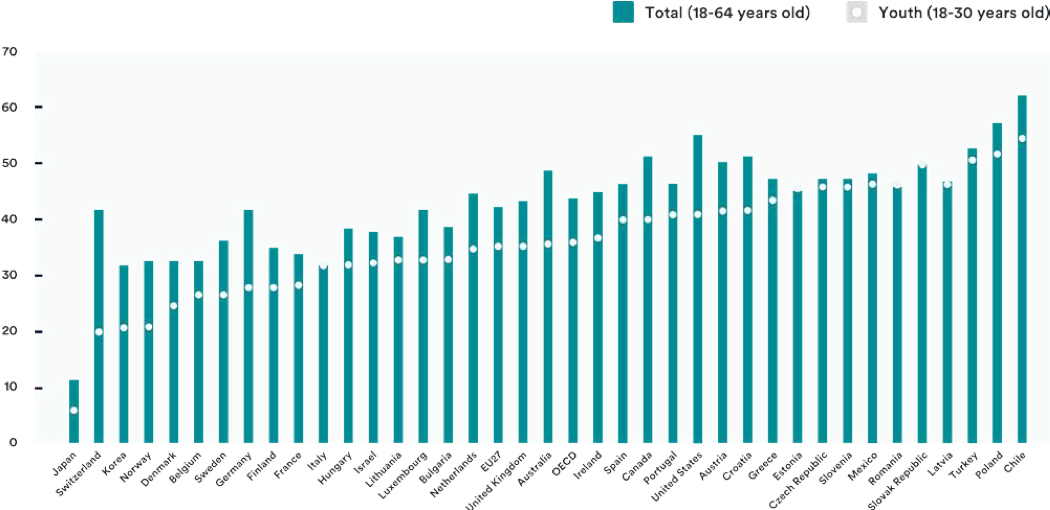

Workers, who have also been affected by this crisis, will experience a special recovery. As the crisis has affected the labor market, inequalities among workers have increased. The OECD states that the share of skilled jobs increased in almost all 38 OECD countries during the pandemic, at the expense of others. The more or less high level of public aid for workers, companies, or certain sectors such as tourism will allow a real revival of activity and will explain the relatively important strength of the economic recovery of the different countries. One of the main challenges is to protect the incomes of the low-skilled workers and to improve training programs and access to the labor market. Training is a key tool to ensure that this recovery is beneficial to the greatest number of people. HR functions will have to do everything possible to meet the qualification needs of the most vulnerable employees and thus enable them to ensure their employability in a world affected by the crisis.

The growth outlook has improved considerably, but it is not guaranteed for all companies. To take advantage of the opportunities created by the anticipated remarkable resumption, we need to make it possible and create its foundations now. After more than a year of living and working differently, companies and employees finally have a clearer goal, a less vague future, although still uncertain. We can look forward to the future, but we need to start preparing now because the resumption will not wait. To seize the opportunity of this renewed growth, organizations will have to rethink their management style and accompany their employees in this return to “normal”.

As life slowly returns to normal around us, we must ask ourselves what effects the crisis has had on our behavior and motivation. The crisis has had a major impact on employees, especially with the widespread use of remote work. Reorganization issues are numerous and decisive for companies’ future, and we must prepare for them now. In order not to miss the resumption and to prepare your employees for the challenges it brings, training is essential. The HR function plays a crucial role because it can provide employees with the necessary resources to take over in the best conditions and to understand the issues they encounter.

To discover Coorpacademy’s courses: